25th October 2023

Critical thinking is one of the most important skills in life. It can help you better understand yourself. It can help you make better decisions. And it is vital for academic success. Yet in many schools, curriculums prioritise a culture of uncritical thinking.

In English classes for example, students are taught to repeat what the teacher says and memorise language from coursebooks. Students get praised for giving correct answers and criticised for mistakes. In school exams, they need to regurgitate memorised information instead of thinking for themselves. Regardless of where you teach, you can integrate critical thinking in classes, even at low levels using simple activities. In this post, we are going to

- consider what critical thinking is

- discuss why language teachers should encourage critical thinking in their classes, and

- look at activities that teachers can use to encourage critical thinking with young learners.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking means different things to different people.

Critical thinking can mean being able to

- analyze and evaluate information before making a judgment.

- see issues from different points of view.

- solve problems creatively.

- make better decisions by considering information.

- avoid jumping to conclusions.

These concepts might appear advanced or abstract. However, even beginner level young learners can practice these skills. Before we look at how to do that, let’s first think about why language teachers should include critical thinking activities in their lessons.

Why should language teachers ‘do’ critical thinking?

You might be thinking, “But my job is to teach English, not critical thinking.” That is a fair point. So why should you bother?

Critical thinking encourages deep processing. That’s a fancy way of saying that the more deeply students think about something, the more likely they are to remember it. As adults we experience this when watching a TV show or reading a book. The more the TV show or book gets us thinking, the better we remember it. That might be why you can remember more about Severance than you can about Baywatch. Hopefully.

Let’s take an example from class. Imagine we’re teaching food vocabulary. We want students to remember the word “hamburger”, so we get them to repeat this twenty times. That’s a lot of practice of the word “hamburger”, but there’s not much (or even any) thinking involved. Compare that to a critical thinking activity. The teacher asks the students to divide the foods into two groups, healthy and unhealthy foods. The teacher asks the students which foods they think are healthy or unhealthy. The teacher listens to the learners, then puts the flashcards in the appropriate columns. The students say “hamburger” less, but they must think more. The more they think, the more the remember. Or, as Daniel Willingham says, “Memory is the residue of thought.”

There are a few other reasons why critical thinking is worth including in your classes. It makes your classes more interesting (both for you and for your students). It also develops skills that students can use in other parts of their lives. Maybe a better question to ask is “Why wouldn’t language teachers do critical thinking activities?”

What critical thinking activities can teachers do with low-level young learners?

Next, let’s look at specific critical thinking activities which you can use with young learners. I’ve put the easiest activities (both for students and teachers) near the start and the more complex ones nearer the end.

Categorizing vocabulary

Take the vocabulary you’ve taught and ask students to categorise it. For example,

- animals could be divided into animals that can and can’t fly

- food could be divided into food that comes from animals and food that comes from plants

- actions could be divided into things people can do and things people can’t do

- transport could be divided into public and private

- body parts could be divided into human and animal.

Students could categorise these individually, or in groups, or as a whole class. The categories themselves can be objective or subjective. The examples above are relatively objective. Below are more subjective examples.

- animals could be divided into pets and non-pets.

- food could be divided into food from here (our country, area, etc.) and from far away (other countries)

- actions could be divided into things most people can do and things most people can’t do

- transport could be divided into environmentally friendly and unfriendly

- clothes could be divided into clothes for boys and clothes for girls

- family members could be divided into young and old.

For low-level monolingual classes, you don’t have to teach students the categories in English. Understanding these in their first language is enough. Higher level students might benefit from learning the categories in English.

Cline

Once you start organising vocabulary into categories it becomes clear that not everything fits neatly into one or the other. Is milk healthy? Not if you drink too much of it. What about rice? It’s not as unhealthy as chocolate, but it’s less healthy than a salad. Which is healthy unless you add too much dressing.

Instead of using categories, students can organise vocabulary on a Cline. This is a scale with, for example, healthy at one end and unhealthy at the other. Students in pairs or groups can organise the vocabulary along the Cline or they can do this with the teacher as a whole class. Some ideas for Clines are:

- clothes from warm to cold

- animals from dangerous to safe

- school subjects from science to art

- hobbies from healthy to unhealthy

- transport from cheap to expensive.

Vocabulary categories

Instead of the teacher providing the categories, give students the vocabulary and ask them to think of the categories themselves. The students are unlikely to know how to say the categories in English. You can help them translate these from their L1 into English. For example, jobs could be divided into

- indoor and outdoor jobs

- dangerous and safe jobs

- low-paid and high-paid jobs

- people facing jobs and non-people facing jobs

After students think of their own categories in groups, ask them to share these with the rest of the class. The class can discuss if they agree with the categorisations.

Quadrants

A quadrant is two Clines combined: one horizontal, and one vertical. So instead of thinking about one property of a word or concept, students think about two. For example, students could divide food into four quadrants, healthy and unhealthy, and foreign and local. In Asia, we might say that fried rice is a local food that’s unhealthy, whereas salad is a foreign food this is healthy. Or for jobs, students could divide these into indoor and outdoor jobs, and dangerous and safe jobs. So, a firefighter might be a dangerous outdoor job, whereas being a banker would be a safe indoor job.

Odd one out

Show students three or four vocabulary items and ask them which is the odd one out. This can be tailored to the age of the students. Three-year-olds will be able to tell you the odd one out from “polar bear”, “car” and “bicycle”. However, choosing words from the same lexical set makes this more challenging. What is the odd one out between a postman, a firefighter and a doctor? Encourage students to pick an odd one out and (most importantly) say the reason. Is it the postman, because they work in the mornings? The firefighter because their work is dangerous? Or the doctor because they work indoors? All answers are acceptable. This activity helps students understand that one question can have several 'right' answers.

Venn diagram

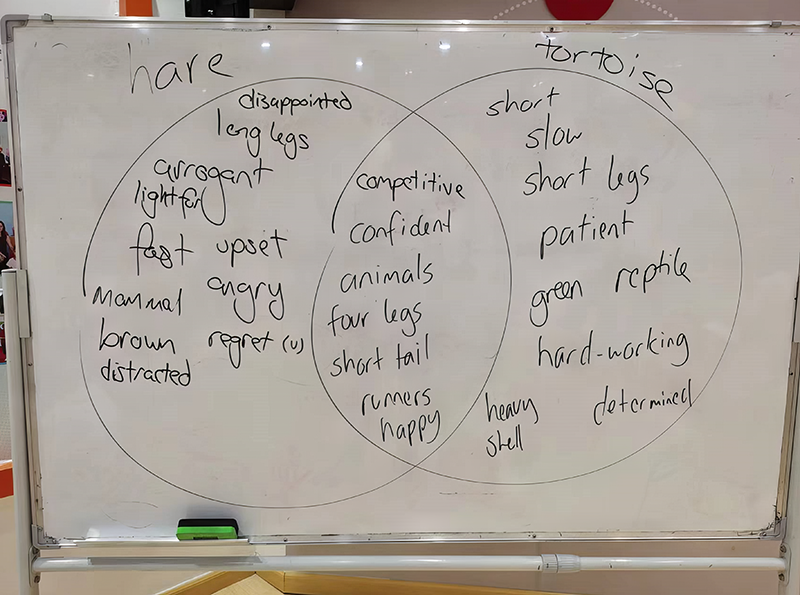

Ask students to compare two concepts using a Venn diagram. They could choose two words from the same lexical set and compare these. Below is an example from students comparing a Hare and a Tortoise.

Students could also compare

- the similarities and differences of two jobs

- two pets, like cats and dogs

- summer and winter clothes

- furniture at home and at school.

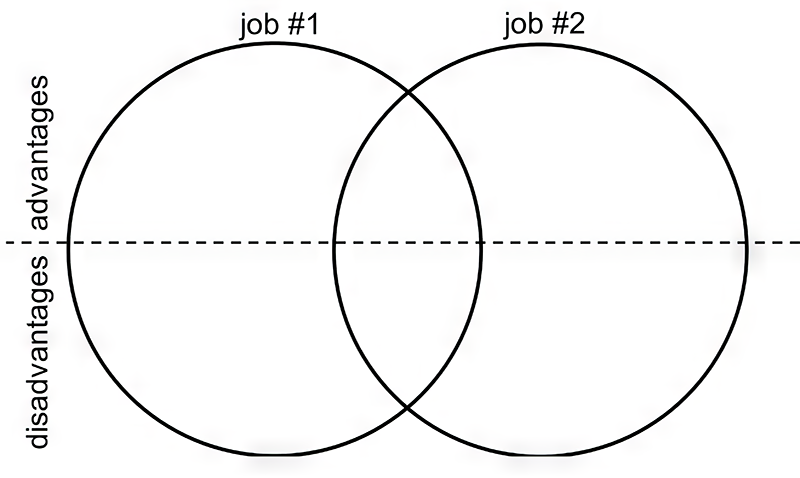

Split Venn Diagram

To make the Venn Diagram more complex, add a dotted line from left to right along the Venn diagram (example below). Students can then compare two aspects of two concepts. For example, students could compare the advantages and disadvantages of two jobs. Or the positive and negative characteristics of two characters from a story.

Pros and Cons

Get students to think about the advantages and disadvantages of a concept related to an item of vocabulary. Students could think about the advantages and disadvantages of:

- doing a job, like being a policeman

- having a pet. This could be a pet in general or having a dog (or an elephant) as a pet

- coming to class by a form of transportation (by car, by bicycle or by bus)

- a hobby, like taking photos or dancing

- learning a language.

Students can compare their lists of advantages and disadvantages with others in the class and decide if they want to revise their own lists. This is a useful decision-making tool for students to learn. However, making informed choices isn’t as simple as counting the number of advantages and disadvantages. That’s where the Tug of War comes in.

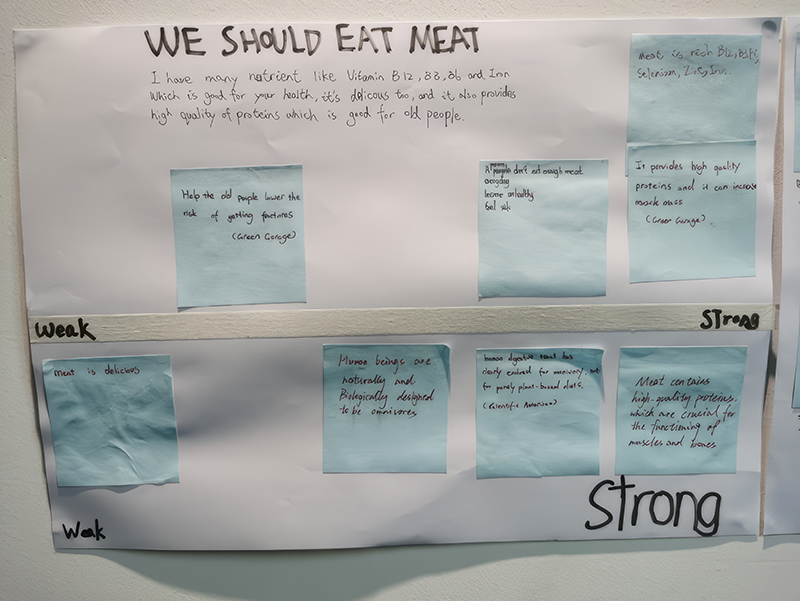

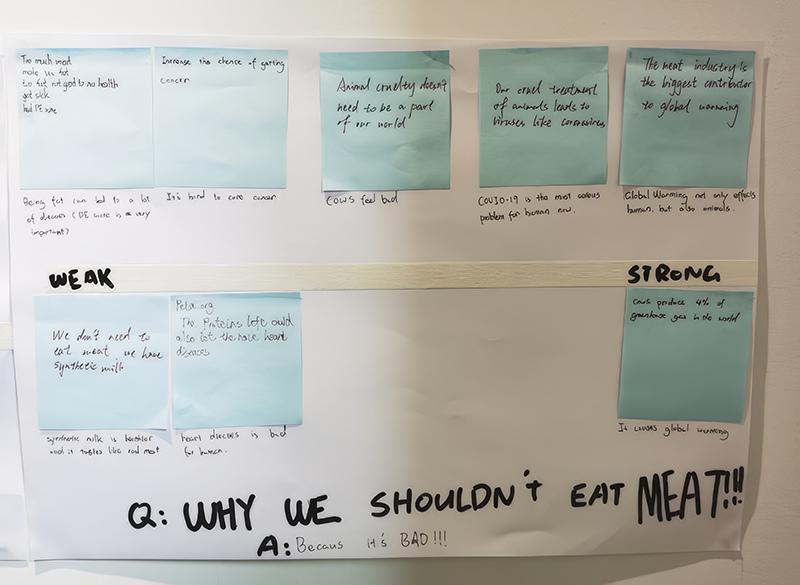

Tug of war

Get students to think about the advantages and disadvantages of a concept related to an item of vocabulary. Instead of simply putting these in columns, get students to decide whether each of these is a strong, medium, or weak advantage/disadvantage. For example, students might decide that a strong advantage of having a pet is company. A weak disadvantage is buying pet food every week.

Draw a line on the board, with “for” and “against” at either end (or “advantage” and “disadvantage”). Tell students the strongest advantages/disadvantages go at the end of the line. The weakest go near the center. Discuss these as a class and encourage students to share different opinions. When the class reaches a consensus, write an advantage/disadvantage on the line. You can then invite students to share their overall opinion on the topic. Below is an example from students about the arguments for and against eating meat.

Viewpoints

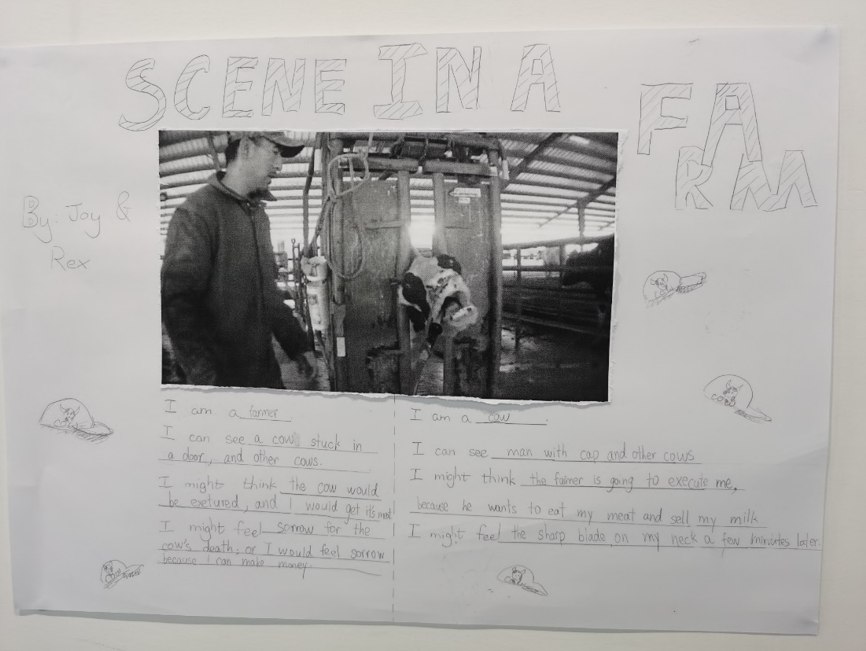

Show students a photo or a picture with different people or things in the image. Ask students to choose two people or objects in the image, draw a thought bubble for each, and write what they are thinking. You could take an image from a coursebook or ask students to add thought bubbles to characters from a story. Below is an example of students taking the perspective of a famer and a cow.

Putting it into Practice

The big challenge with doing critical thinking with low-level young learners, is that the students won’t have the vocabulary (or the grammar) to be able to do the activities. There are some ways around that.

If you do these activities in groups, your students might end up using their L1 (first language) a lot. To ensure that some English gets used, give students the written form of the vocabulary rather than pictures to organise or categorise. Students will at least need to think about the meaning of the written form. If students categorise pictures of foods, they might not use any English whatsoever.

You can do these activities as whole class activities, where the teacher leads the students. This gives the students input. If the students comment in their first language, the teacher (or assistant teacher) can translate their comments into English. The teacher can encourage students to use the vocabulary by adjusting the questions they ask. For example, imagine we’re putting food on a Cline, from healthy at one end to unhealthy at the other. The teacher could ask “Where does hamburger go?” The students might then point to somewhere on the Cline. The students heard the “hamburger” but didn’t need to say anything, just point. To encourage more speaking, the teacher could say “What food goes here?” while pointing to the unhealthy end of the Cline. Students might then put up their hands and say, “A hamburger”. Now students are thinking deeply and using English to communicate.

Are you looking for a Teaching Young Learners Course?

This 20 hour course provides practical guidance on classroom management, materials design, and the theory of language teaching to young learners.