8th November 2016

One of the more common beliefs that teachers and students bring to the classroom, especially in Hong Kong (which tends to favour classroom activities based on memorization and declarative, as opposed to procedural knowledge) is an obsession with grammar.

Yes but they need to know the grammar, teachers often say.

Yes, the students didn’t necessarily write very much, but I taught the grammar well, they might suggest.

My son really needs to work on his grammar, the father of the strongest student in a primary 6 class once told me.

This is because language = grammar + words...right? Learn the rules that govern how language “works” and then plug in the other words you need and away you go: error-free, situationally appropriate language use at your disposal, whatever the time of day. Right?

In actual fact, that may not be entirely true. At least, it may not be the most useful way of thinking about language. A recent article on The Atlantic has been doing the rounds this month, claiming that “we need to teach students grammar by letting them write”, which attempts to get to the heart of the myth that grammar is the most important aspect of learning a language – and one which, in the long run, might actually significantly reduce your ability to speak and produce that language to a high level.

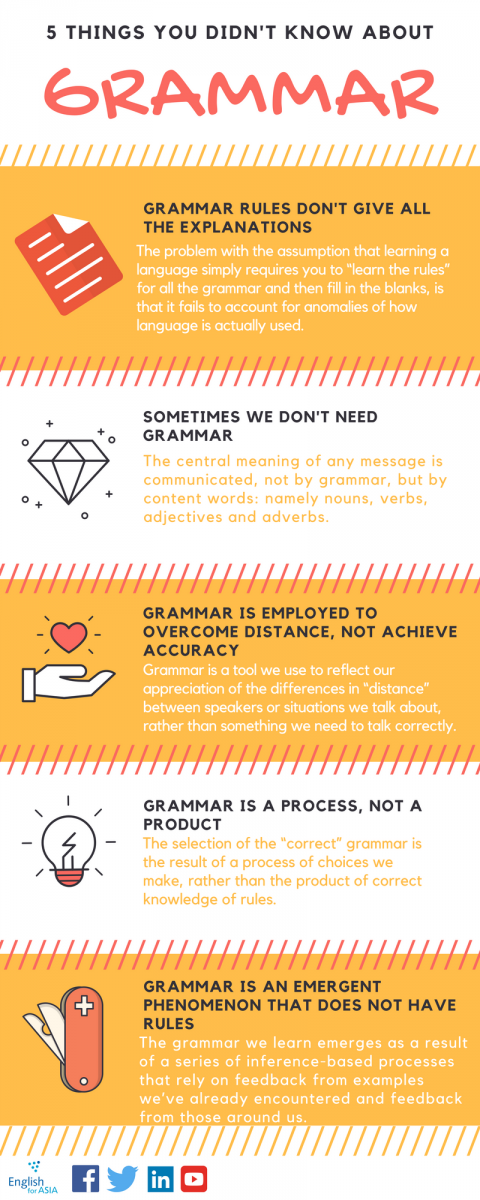

In this post, we look at five alternative views of grammar that suggest the heavy emphasis on grammatical-based language study, or the “grammar McNugget” view of language as Scott Thornbury calls it. We don’t necessarily argue that all of these are the “right” view of grammar, but we do suggest that grammar is far more complex than a “language = grammar + words” approach might lead us to believe.

In its simplest form, we will look at basic examples to show why grammar “rules” are often arbitrary, and therefore not actually all that useful for learning how language works. At the extreme, we will ask what if….just….what if, there were no grammar rules at all? What if Morpheus we told you that the “rules” of grammar were merely our perception of order in a system that was, in essence, highly irregular?

Quickly, before your head explodes, strap yourselves in for an existential journey that will make your day and just maybe, reshape the way you think about grammar.

1) Grammar rules don't give us all the explanations for using language correctly

One of the arguments often presented in favour of learning grammar rules is that they make language easier to understand: they give us, and our learners a system to help them make sense of complex meanings and structures. This may be true, and it may be very convenient…..but it can also be limiting.

The problem with the assumption that learning a language simply requires you to “learn the rules” for all the grammar and then fill in the blanks, is that it fails to account for anomalies of how language is actually used. For example….why do we say It’s a quarter to three?

According to the “rules” we might, very logically, also say:

-

It’s forty five past two

-

It’s fifteen to three

-

It’s forty five after two

-

It's forty five more than two

-

It’s three less fifteen.

There is no grammatical or syntactical rule to explain why these are not satisfactory in English other than the fact that they are simply not how you tell the time. To do this, you need set phrases, or chunks, and you need to put these together in a way that reflects whether there is more, or less than half an hour remaining before the next hour arrives. In this way, we might look at phrases, rather than patterns of syntax as a way to teach this language:

-

Quarter to

-

Quarter past

-

Half past

-

Ten past

-

Ten to

2) Sometimes we don't need grammar. At all.

Indeed, next time you’re at the market in Bangkok, trying to negotiate the price on three cheap shirts for your friends, how much knowledge of the correct syntax and tense system that govern the Thai language will you employ? Does this stop you getting your ideas across?

Consider the following conversation:

- Coffee?

- Please!

- Milk?

- No.

- Sugar?

- Two please.

A perfectly reasonable conversation between what could well be two people who know each other quite well (we’ll look at why this conversation wouldn’t necessarily be appropriate between a customer and a barista in a café later) yet there is practically nothing but individual items of vocabulary, with key grammatical meaning communicated by the pronunciation of some of the turns. No verbs, no tenses, no complex inversion of subject and objects to form questions. So what’s going on?

This is, in fact, the way many low-level students might be inclined to communicate when they first learn a language, or how a tourist in Thailand might sound trying to negotiate the complex intricacies of bargaining in the developing world. That said, we can see from this example that most of the central meaning of any message is communicated, not by grammar, but by content words: namely nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs.

Ah! You say, But you need to know grammar in order to use verbs!

Yes, this is partly true – but whether someone says two please or yes, I’ll have two please or I’d like two, if it’s not too much bother, please – the key message is the same.

3) Grammar is employed to overcome distance, not achieve accuracy.

So, looking at our example above, how can we say that it is acceptable, but not acceptable at the same time? Well this might be partly explained by challenging a pre-existing assumption that correct grammar usage is an important indicator of accuracy in a language. Well, we would argue that using grammar correctly is not the reason why people are accurate when they speak, and so correct grammar usage is the end result of knowing how to use language.

This is important because it might suggest that in fact grammar shouldn’t be the starting point of learning a language, but rather it ought to be what happens as a result of learning the language.

Consider these three examples:

-

Would you mind opening the door?

-

He would never listen to me as a child.

-

Would you do it if you had the chance?

Each of these three sentences contain examples of the past form of the verb “will” and “have”: would and had. However, in which sentence is the speaker actually talking about the past? Number 2, right?

What is the purpose of using the past forms in these other examples? In number one, we are choosing to say “would you mind” as opposed to “do you mind” or even simply “open the door”, each of which has its own unique meaning and implication. By adding these complexities and subtleties, we are in effect creating distance, so as to be perceived as more polite, or less direct, and in many social situations this is an important part of using language appropriately because it shows that we are sensitive to those around us, and the possible ways in which the alternative (but grammatically correct) options might be interpreted. So we can say in this instance, we are trying to create social distance by choosing certain grammar options over others.

In example number 3, what time period exactly are we referring to? Is it the past? The present? The future? All of the above? In this case, we might say that this sentence refers to all time (except perhaps the past) – or that, more specifically, we are using the past form here – would – to create distance from reality. That is, we are talking about something that is purely hypothetical, or removed from reality (or my perception of reality).

But does this just apply to the use of the past forms of English verbs? Not really. Consider the different ways you might ask someone to pass you the salt:

-

Salt!

-

Salt, please!

-

I’d like the salt.

-

If it’s not too much trouble, would you possibly mind asking the gentleman next to you if he would be able to reach across and lend me…….

So we can make a generalization here: that grammar is a tool we use to reflect our appreciation of the differences in “distance” between speakers or situations we talk about, rather than something we need to talk correctly. Afterall, of the examples above, many of them are appropriate in the same situation (whether you’re at a friend’s house for dinner, or at a fancy restaurant). The difference in appropriateness is really dependent on how much you feel the need to acknowledge the “distance” between you and those you talk to.

4) Grammar can be seen as a process, not a product.

When we look at the way children learn their first language, we see that children often learn to communicate with a limited understanding of the grammatical system they are using. This might result in utterances like this:

-

Mummy! Man, walking fast

Although correct, and the meaning is clear, it doesn’t give us the subtle differences of meaning that the child may be wishing to communicate. Gradually, through sufficient exposure to authentic language, caregiver talk, or motherese, the child might eventually apply, test and adapt his language to say something like:

-

- Mummy! That man is walking very fast!

Or perhaps:

-

- Mummy! That man can walk very fast!

Or even:

-

- Mummy! That man is trying to walk very fast!

While this is true for young children, how does it apply to mature speakers of a language. We might look at the way the passive form is used in English as an example. Take a look at these examples:

- He was saved by a passerby from his burning car.

- A passerby saved the man from his burning car.

Both of these sentences are correct. However, which of them is the most logical sentence to follow this one:

- A young man had a lucky escape yesterday.

- __________________________________

Though both exampled are correct, the choice of which sentence fits best is not a random one. The correct sentence depends on the choices we make implicitly as a speaker in determining what (the man or the passerby) is the most appropriate focus of the following sentence – i.e. the thing that should attract most of our attention ought to be in the “topic” position of the sentence.

This suggests that the selection of the “correct” grammar is the result of a process of choices we make, rather than the product of correct knowledge of rules. In this way, grammar can be seen as a choice between various options, not a set of hard and fast rules, and it is the result of considering and making these choices that means grammar can be seen by some as a process, known as “grammaring”.

5) Grammar can be seen as an emergent phenomenon that does not have rules

Finally, we look at possibly the most contentious claim yet: what if the “rules” of grammar are nothing but an illusion of order?

This is exactly what connectionist theories of learning suggest about the perception of rules in complex systems like language learning. Scott Thornbury explains that, based on computer science models that replicate neural networks, learning results as we identify irregularities in data that we encounter. He gives the example of learning the “rule” of –ed to form the past. In a connectionist model of learning, we wouldn’t learn the rule, but rather, we might use the examples of verbs that are more or less strongly associated with, or similar to the rule. So for example, when we encounter the verb bring and its past form brought, we consider how similar it is to other verbs we have encountered: very different to the verb watch, but closer in form to the verb teach.

So, when we encounter utterances and examples of language, our “pattern-hungry brain” works tirelessly to assimilate these new forms and examples into the “patterns” we have previously encountered, and so the grammar we learn is not transmitted to us from a teacher or a book: it emerges as a result of a series of inference-based processes that rely on feedback from examples we’ve already encountered and feedback from those around us. The result is our own, individual (and varied) perceptions of well-ordered rules.

By this stage, if you don’t feel a bit like Neo choosing between the red pill and the blue pill – you’re well on your way to becoming grammar teaching's own emodiment of "The Chosen One".

So next time someone tells you they are going to teach a grammar lesson, think very carefully what you say them.

References:

• Uncovering Grammar, Thornbury

• Teaching Lexically, Dellar & Walkley