20th October 2016

When I was 5, I had a piano teacher who rapped my knuckles and told me off sternly when I didn’t practice enough. When she asked me to be a part of her annual recital, I burst into tears and shook my head, overcome with fear at failing in front of an audience. When I was 12, I had a maths teacher who was ex-Army, who would scream at us if we asked our friends for help. He once was writing something on the board with chalk, when he heard someone whispering, and quick as an arrow, he turned and THREW that chalk at the student and hit him on the head. Needless to say, I hated maths and was terrified of him and asking him for help when I had problems understanding the subject. We’ve all been there and we all have our own horror stories about teachers who may have scarred us for life.

When I first became a teacher, I told myself I wouldn’t become one of those terrible, angry teachers, until my first day teaching in a secondary school. I was 22, and working with a teaching agency, who sent me out to parts of Hong Kong, for short teaching jobs. One of the schools was, at the time, considered to be one of the weakest, in one of the poorest districts of Kowloon, in a housing estate. There were 45-50 students per class and it was mixed ages, from 11-14. I remember being terrified and thinking that I needed to assert my authority, the only way I knew how, by raising my voice and being as restrictive as possible.

It didn’t end well. By the end of the day, my throat was hoarse from shouting and I hadn’t achieved anything. The students didn’t pay attention or care who I was, and did their own thing anyway. By the end of term, I was a ragged mess, stressed out and angry, feeling like a complete wreck, I swore off teaching secondary altogether, putting it down to me not understanding and enjoying teaching teenagers. In fact, I was only half right – as a teacher, I hadn’t understood teenagers (despite being so close in age to them), because I hadn’t taken the time to research what motivates them, what praise they might respond to, what they didn’t like about the subject, etc.

Many years later, during my DELTA in the UK, my course tutor told our class during a session on behavior management, that once you raise your voice as a teacher, you’ve lost. Meaning that, students will either feel scared, angry or indifferent to you and your control has diminished because you have taken away whatever is fun and interesting about English, and made it a trial to suffer through. This stayed with me a long time.

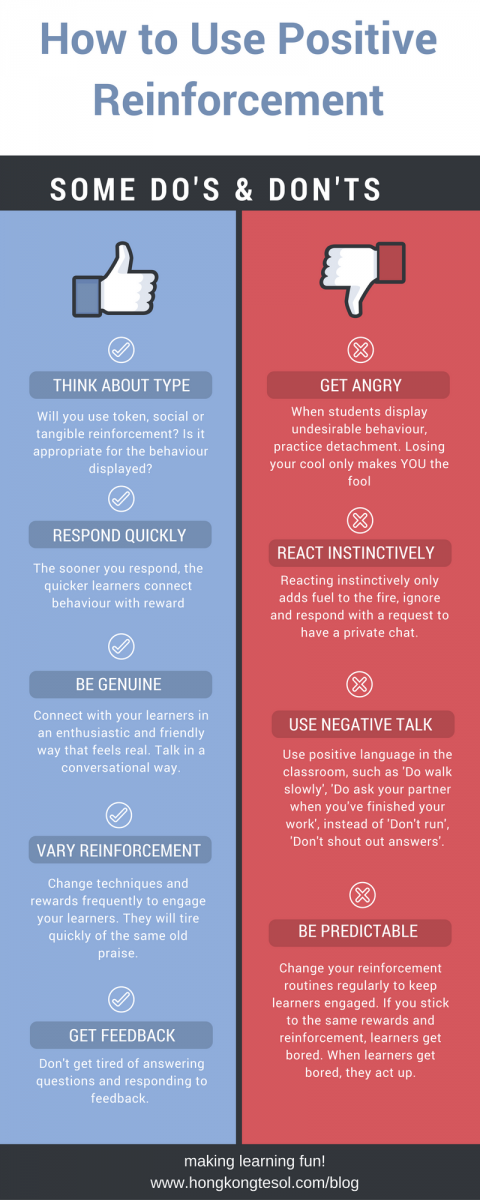

Positive reinforcement is a very effective method of classroom management. The crux of positive reinforcement is that by rewarding good behaviour and ignoring (yes, hard to believe and suffer, but necessary) bad behavior, teachers will be able to change learners’ behavior for the better by conditioning them to respond in a specific way. The reason why is simple, it builds confidence and rapport. When a learner feels confident and happy, they generally respond by showing the desired behavior. It took me many years of teaching learners of all levels and ages to build up a bank of techniques that works. There are a few things to consider first.

Age

What a lower primary aged child will respond to well, such as stickers or gold stars, they will not have the same effect on a college student. The key is knowing what is suitable and appropriate for the learners’ ages (and run it by a fellow teacher or principal first to make sure it’s acceptable). No, candy is never a good one for small children (allergies, etc).

Types of reinforcement

How you reinforce positive behavior is important. Will you use a point system (or token reinforcement) which can be exchanged for something later on? Perhaps praise (social reinforcement) expressed orally or through comments on written work is needed, e.g. a quick ‘Nice one’ or ‘Good job’ may pull a student’s attention back to the task? Or maybe you bring out the big guns and use treats, toys, stationary, etc as hard currency (also known as tangible reinforcement)?

Whatever you choose, make sure it is appropriate for the behavior and task. For example, a student who has spent time on a presentation with good materials and expresses themself well would probably deserve a tangible reward, if the presentation was something outside normal routine, if perhaps it was the final task in a month-long project. If learners were doing short oral presentations daily or weekly, perhaps social or token reinforcement would be better.

Response time

The basic principle behind Pavlov's dogs was that delaying rewards decreases the chances of the behaviour reoccuring. So, the quicker positive behavior is displayed and responded to, the stronger the connection between behavior and reward for the learner. So don’t hold back on the rewards, let learners know immediately when they’ve done something right and be enthusiastic about it. Be excited for their learning and they will be excited too.

Vary reinforcement

As with anything, if the same reward is given, it no longer becomes a reward or interesting and it loses its value. Change your techniques and rewards frequently.

Here are some useful ways to respond to your learners:

1) Token reinforcement

I put young learners up to the age of 12-13, in groups from the beginning of the lesson and ask them to choose their own team names. The group are then responsible for getting as many points during the lesson as possible – with points going for EVERYTHING, sitting down / working together nicely, putting hands in the air to answer, for people standing up and giving the correct answers clearly, for giving answers in the desired way (not shouting them out), for taking out and putting away classroom items, for sharing, turn-taking, for learners being creative, for helping each other, you name it. Basically any behavior that you want to see in the classroom. I generally finish the lesson 10 minutes early to allow the winners to choose an English game to play, or song to YouTube and sing along to, funny 5 minute cartoon, a story to read aloud for the whole class to participate in.

Why it works: This is a classic behaviour-reward approach. Giving concrete, visible, tangible rewards to children can make it clearer to them that their behaviour is good and you'd like to see more of it.

2) Token reinforcement

This can work on an individual level by awarding particularly challenging students with points for a weekly basis which they get to trade in for stationary, treat, book of choice to read in class quiet time, play a board game, drawing time, computer time, etc. Talk to the principal to see if they would give you a minimal budget to buy treats - $10 stores are your best bet for buying little treats or stationary in bulk.

3) Social reinforcement

Remember to describe the positive behavior while giving praise so that learners make a connection to their behavior. Focus on what the student did right and state it in positive language. For example, “That was a wonderful paragraph you wrote because …”

Why it works: Not only is it important to make it clear to learners that their behaviour is good, but often it's important to make it clear in precise terms why you feel happy about a particular behaviour. Giving concrete reasons why you're happy helps children to associate your reward with the exact behaviour they displayed, and helps children to understand why it was good, so they can apply it to other situations.

4) Social reinforcement

Accredit success to their effort and ability because this suggests that similar successes can be expected in the future. For example, “Your studying really showed. That’s a good mark on your spelling test. It shows you really worked hard.” This type of praise also helps students get a better understanding of their own skills.

5) Social / tangible reinforcement

If you are unable to give treats, try these privileges instead, such sitting in a special place in the classroom (works very well with very young learners and learners up to 7 years old), or having extra time, with the teacher or a peer (beneficial for older learners) at the end of the lesson for a conversation, or to have extra time for a special activity.

Why it works: It's important to make sure that rewards of any kind are meaningful to the students. You don't need to work in a well-resourced staff room to offer rewards, and in fact it can be counter-productive to set up classroom economies where children expect material rewards in return for positive behaviour. Negotiating options that students feel would be suitable rewards, like conditions for homework or extra reading time, can be just as meaningful.

6) Bonus: Find examplar students

Use positive language to demonstrate what you expect. When you notice students doing what you have asked, tell everybody about it. "That's very good sitting, Julia. Simon, I'd like you to sit like Julia is sitting please".

Why it works: Using positive language forces you to describe the behaviour you want, which makes it more concrete for learners to moderate their own behaviour. It also avoids a situation where you repeatedly have to ask the same student NOT to do the same thing again and again, thereby limiting the potential for conflict with particular students and praising good students at the same time.

What positive reinforcement methods do you use in the classroom?

For professional development classes on behavior management, check out our upcoming TEFL teacher training workshops in Hong Kong.

For more about positive reinforcement, check these articles out:

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-reinforcement-2795414

http://www.learnalberta.ca/content/inspb1/html/6_positivereinforcement.html