9th July 2019

So you're looking for writing lesson plan ideas, and you're not sure where to start.

Does any of this sound familiar?

Yes, but writing is boring.

Is it?

Sure, but writing could be time spent in class doing fun speaking tasks.

Who said you can’t do both?

But my students get more out of class from interactive activities.

Exactly – writing lessons don’t have to conform to any of these assumptions. Indeed, there are many reasons why giving students a written task may be better for their language development than spoken tasks.

Got some spare time for professional development? Watch our webinar on writing for young learners below.

Firstly, written language is permanent. It creates a record of language that can be manipulated, edited, changed and commented on. Whereas when students are speaking everything happens at once and then the language used disappears into distant memories. That is to say that when you ask someone to speak, especially in a second language there are many things happening at once: you first have to identify what someone is saying to you, then you have to formulate a response by recalling chunks of languages and drawing on your knowledge of syntax and pronunciation, if you don’t know a word you then have to find a way to communicate that idea (i.e. paraphrase), then you have to articulate it and finally, you have to monitor what you are saying for errors and accuracy. Most of this is an unconscious process, but because it tends to happen in a very short time scale, it places speakers under a very high cognitive load, which means you actually have fewer cognitive resources for attending to errors, accuracy and the content of what others are saying. However when language is written down, while similar processes apply, the time you have to run through them is largely extended because students can easily see and work with the language they have produced: it’s on the page!

Secondly, well-delivered writing lessons will include multiple stages that focus on interaction and collaboration. Some of the most important elements to successful writing lessons are often overlooked. These include: planning content, peer correction and collaborative writing. Giving students the chance to plan what they are going to say (rather than simply saying: “now start writing”) is a key stage in the process of writing: it is a behavior that many successful writers rely on to organize their ideas. In second language classrooms, it also means students don’t need to think of two things (i.e. what they want to say and the target forms they wish to use to do so) at the same time, thus freeing up those invaluable cognitive resources for other processes during a task.

Likewise, asking students to peer correct provides another stage in which students can interact in a meaningful and reflective way. This doesn’t mean telling your students to “read your partner’s letter and decide if it’s good or bad”. A well-planned correction stage will consider the key ingredients of the text the students are working with (e.g. address, salutation, stating the reason for writing, clarifying the problem, stating a desired outcome, closing….if you’re writing a letter) and also some of the key target phrases for each of these components of the text. It then make sense for students to look for examples of these linguistic features when editing (they won’t be able to edit and correct everything) because if they could, they wouldn’t need to be in your class, would they? So giving students checklists, asking them to tick, circle, underline, box…these are all concrete ways you can encourage the students to engage in the writing process and develop their ability to comment on and monitor language use and appropriacy.

Who should do the writing: do students really need to write one text each in a writing lesson?

How many books, articles, stories, novels, movies or songs can you think of that have been written by more than one person? So, why should we impose a one student, one text policy at all times? This is even more important when students are paired up to plan the content of their texts in preparation for writing, which they can then continually discuss and refine as they produce a text in pairs. It’s even possible to create texts in small groups – by providing students with a large template on A3 or A2, you can then assign different roles to the students so that they all contribute in some way to the production of the text.

When teaching writing, keep in mind the CLOGS analysis

We need to have an understanding of Content, Layout, Organisation, Grammar and lexis, and Style of a text in order to produce it according to the conventions of that genre. So, one student could be assigned the role of writer (or even two, by having them work on different parts of a text for example), one person could be responsible for the layout of the information on the page (where does the heading go, how big will the paragraphs be?), one student could be assigned the role of editor (check for use of target language highlighted on the board, is the vocabulary used appropriate to the style and tone of the text?) and one person could be assigned the role of content manager (which information need to be prioritized in the text, which information should come first?).

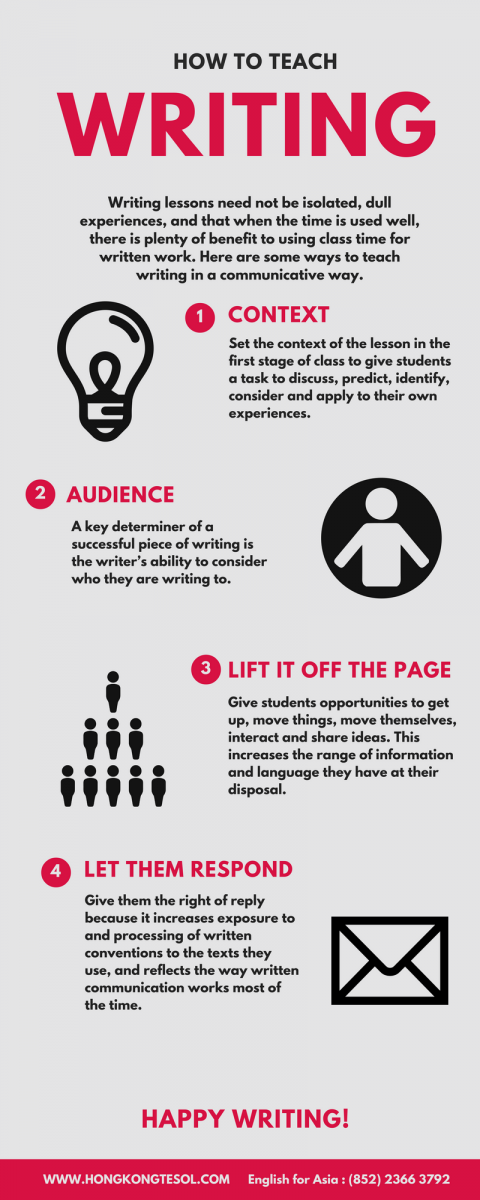

So with this in mind, hopefully you are starting to appreciate that writing lessons need not be isolated, dull experiences, and that when the time is used well, there is plenty of benefit to using class time for written work. At the end of the day, you need to remember that just because students are using a pen or pencil, it doesn’t mean they are practicing their writing skills. Writing skills development assumes that the students are working towards creating a text that approximates as closely as possible, the conventions of the genre (following the CLOGS analysis!).

But how do you stage a writing lesson? At the end of the day, if you want to teach writing, then you need to model effective writing for your students.

It’s one thing to analyse the text as a teacher, but it’s a whole other thing to get the students to pay attention and notice the language and textual features you’re hoping to work with.

So here are a few key ideas that will help bring your writing lessons to life.

1) Context

As always with language teaching, context is everything. In communicative language teaching, this means establishing the who, what, where, why and how. You need to consider who the people are, what they’re trying to achieve, where they are, why they are communicating in this way and how they are doing so. Often, communication is seen a tool to solve problems or close the gap between speakers or writers. This means when we set the context of our lesson in the first stage of class, we need to give students a task to discuss, predict, identify, consider and apply to their own experiences.

So next time you plan your writing lessons, you could try these ideas:

-

Displaying a picture and asking students to predict what the problems is and how the people are feeling. You could extend and have students anticipate examples of language they might see or use in the text.

-

Giving students vocabulary, or features from the text and have them rank them. For example, students could be given a list of different ways of making complains and rank them according to appropriacy in different situations, or for different problems.

-

Presenting students with a problem (i.e. you bought a new toy but it doesn’t work) and have them brainstorm potential solutions.

-

Reading students a story and stop before the last page of the book. Have them predict what comes next (and possibly write the final stages of the story).

2) Who is the text for?

A key determiner of a successful piece of writing is the writer’s ability to consider who they are writing to. This requires an understanding of the way culture governs relationships and sensitivity to the way language influences this. Perhaps one way of thinking about this is not to focus so much on what people need to say in their writing, but why they might choose one form of language over another.

You might like to incorporate this into your writing lessons by:

-

Adding preparation stages in which students first brainstorm, plan and discuss the content that they need to include in a text. Then, brainstorm features of the person they intend to give or send the text to. This might include having them write or map out a brief profile of their intended reader and include things like their name, their age, how they might feel after reading key parts of the text, what they might expect to find in the text they are reading, what their relationship is to the person writing the text, where and when they might be when they read the text.

-

Give students a negative example. This can be a fun way to demonstrate a task by showing the students what you don’t want them to do. After students read the bad model, guide them and have them discuss their own reactions as readers: how did you feel? Which part of the text seemed to be the least appropriate? Why did ____ make you feel this way? Would someone of a different age/culture/role/relationship respond in the same way? What alternatives might the writer have to communicate the same idea?

-

Split your writing lessons into two groups, and have them write the same text to very different people. You might ask them to write an invitation to their teacher vs their cousin, or have them write a information brochure about a new service/activity group for a new students to the school vs. and existing student. This will give you a chance to examine and compare the differences in language choices each group makes, and consider which ones are more appropriate, and, importantly, why.

3) Lift it off the page

This is a mantra I’ve kept with me since my initial teacher training: lifting activities, tasks and words off the page can have a huge impact in contributing to the variety and pacing of a lesson. The good thing is, this can happen at almost any stage – and by giving students a chance to get up, move thing, move themselves, interact and share ideas, you may well be increasing the range of information and language students have at their disposal for later production stages in the lesson.

Some ways of doing this might include:

-

Pictures or visuals used to convey meaning key vocabulary. Students can then put them on the board in the order they encounter them in the text. Why not have students then create a similar task for vocabulary they use in their own written texts, and as students read each other’s work they have a mini-vocab task to accompany it!

-

Peer discussions – any response-to-text task lends itself well to group interaction. This could simply be a brief pair discussion, and then whole class task where students need to find how many of their classmates agreed with them.

-

Collaborative writing tasks. It amazes me how often this suggestion confuses people, in a way that seems to contradict many pre-conceived notions of what a writing task ought to be. So next time you have students complete a writing task, why not ask them to write one text between two or three? This could be through assigning students different roles, as mentioned before, or simply having two students plan and produce a text together. You can increase collaboration by having students display, comment on and edit each other’s work – though be careful with this, as asking students to “read and check” is an unreasonable ask. Give them specific things to look for!

4) Give the students a chance to reply

The right of reply is often overlooked in writing lessons, I suspect, because of a lack of time. But just as a speaking task is dependent on one person making a verbal contribution and the others in the group responding, allowing students to form written replies increases exposure to and processing of written conventions to the texts you work with, and it also reflects the way written communication works much of the time in authentic contexts. Think: emails, texts, facebook posts, blog comments, letters to the editor. These all require written, interactive communication to be sustained.

Some of the ways I encourage this in my class include:

-

Using templates. By printing off email templates, or facebook comment templates, it makes it easier for students to write back to their partner and display their responses in a clearer and organized way, especially when the written exchange is displayed in the classroom as the lesson progresses.

-

Asking questions. You can increase interactive written elements to process writing lessons by first, having students write their final texts using every second line (leaving plenty of space to add comments). Students then use post-it notes to write three questions to their partner about the information in their text, and post the questions on their partners’ text. Students then take back their original work and re-edit to incorporate some of the comments and questions they received. Remember the questions need to be about content not just language accuracy.

Do you have any ideas for making your lessons more interactive?

Considering a Trinity CertTESOL qualification? The introductory module of the CertTESOL course is now available as a standalone fully online course – the TESOL Starter course.